They also bird who only sit and wait…

This article first appeared in Birdwatching

I am known for my whinging. A well known, follicley-challenged TV naturalist once said how much he missed my viper wit when I wasn’t asked to take part in ‘Just a Linnet’ at the British Bird Fair. But, just for once, I am going to replace my normal acidic whine for a measured tone and open my inner most secrets to an agog nation… or at least whoever cares to listen to me mumble about how I watch birds.

This is not provoked by my normal tendency to pontificate, but more a desire to share, for the benefit of the less able, less fit or more overweight among you, that birding can be long distance, slow, silent, sedentary and low key.

The tendency for the popular press to call our obsession twitching, whether we chase rarities nationwide or just watch sparrows in the backyard, always irks me. Yet it is not the only misunderstanding of what we do and how we do it.

Birders are expected to stride forth across the moors or hike through a forest ameliorating their nerdiness by becoming super fit and self-righteous. As if, there is a right way to bird that brushes away cobwebs accumulated in study, or washes away the aroma of anorak (attendant upon us boy-scouts and girl-guides who sport attainment birding badges and overweight optics).

I have developed a birding style necessitated by disability, and my predisposition to indolence. I cannot walk very far on a good day, and hardly at all on a bad one. Mind you, if I could, I very much doubt that I would. I blame my corpulence on the lack of exercise that arthritis dictates, without mentioning that the dictat doesn’t require the copious ingesting of cake, curry and chocolate!

Why do birders carry scopes?

A simple question? Not one bit of it! From my own observations I have to conclude that they carry them as a form of weight training. Do they hate the manufacturer’s continuing efforts to reduce the weight of scopes and bins. Because they seem intent on carrying them as far as they can, for as long as possible, just to strengthen their abs and pecs and other body bits I’ve long ceased to find about my person.

I, on the other hand, use my optics to bring birds closer to me! I look for a high point, such as a ramp overlooking a scrape, and scan the view with my naked eyes. If I spot a movement or hear a call the binoculars swing into action. If they are insufficient to the task, out comes the scope and, low and behold, I see the quarry in all its glory!

Call me silly if you will, but isn’t this the whole point of having thousands of pounds worth of burnished metal and polished glass? I don’t need to creep so near to a bird that I can see what it ate for yesterday’s breakfast. Nor afterward expound over a pint just how close my binoculars can focus down! Notwithstanding this seemingly obvious characteristic of magnifying lenses, many of our tribe have to carry them as close as possible to the birds. Indeed, it seems to be compulsory that the rarer the bird, the closer an encounter is supposed to become. How many times have you been to a twitch to see the crowd rush forward every time a bird breaks cover? It can’t be that birders are trying to get a better view, because the rarity inevitably gets flushed further away. Stand your ground and, usually, the poor blighter will sigh its avian sigh and settle to rest, feed or flit in plain sight.

I went to Dungeness on the day a Crested Lark turned up in the ‘desert’; the vast area of shingle close to the observatory. Hawkeye (my wife, Maggie) and I watched a great semi-circle of a crowd move in ever closer to its last observed location…

“Move the car” she said. “Drive round to the other side of the rail-track opposite the gap in their circle”.

Never one to cross ‘she who must be obeyed’ I did as directed. I parked and we got out of the car just as the jaws of the circle were closing and the lark slipped through and flew steadily towards us. It landed 10 feet away and paused long enough for us to raise our optics and get a decent view, then flew off as the narrow-gauge train came by!

Yet these birders are happy to hone their long-distance skills sea-watching. In fact, it is generally accepted that the further away a bird is when identified, the better the observer is at our spotting sport. The very same fellow who picks up a Sabine’s Gull three miles out, or identifies an Arctic Skua shearing below a winter swell, whilst someone throws buckets of brine in his face, is he who must creep to within touching distance of a Great Bustard just to be sure it isn’t a Great Tit!

Take an arthritic’s tip – optics were invented to obviate trekking!

Woodland wandering versus lazing in wait…

Did I mention that I can’t walk very far? Apart from the fact that the pain is off-putting and my joints cease up like unused plumbing, it is worrying to be more than a kitkat’s length from the car when the munchies strike.

So how do I manage in the woods when clearly one has to quarter its acres to pin down Paridae or harry Hawfinches?

Some of you will have twigged (sorry) already. If one sits, back against a tree, or just stand quietly in the shadows, chances are the birds will come to you. OK, you might first have to walk a hundred yards into the wild wood, but you are just as likely to connect there as a mile further along, if the habitat is right. In winter some birds flock and move through woods like a wave of antbirds in the neotropics.

Some years ago I regularly traveled from London to Bournemouth to see the outlaws. As well as I got on with my mum-in-law, there were times when I needed to delay the forthcoming pleasure of guessing her formula of sand to cement that her steak and kidney pie needed to create its perfect crust. So I would dally a little in the new forest breaking the journey, hoping for a few woodland species unlikely to turn up in London’s Westbourne Grove.

I used to pull into one of the caravan carparks scattered around the area. I found that if you drove past the last tent, wound down the windows and turned off the engine then scattered peanuts on a tree stump, the Nuthatches would magically appear. As they got into the business of ferrying away these free offerings the other birds would relax and forage freely. So, from the safety of my mobile hide I could see tail-twitching Redstarts and Hawfinches turning over the beechmast or even a Lesser-spotted Woodpecker investigating the under-storey. The same technique employed in gorse-surrounded carparks usually delivered Dartford Warblers and on one memorable occasion both Firecrest and Crossbills in the only stand of Scots Pine for miles.

Picking the right spot

Do not confine your hobby to the spots selected by whoever wrote the ‘Where to Watch’ guide for your county. Yes, they will have combined their skills with the accumulated knowledge of locals, but they don’t mention every place where birds can be seen. Indeed, if, like me, you are lucky enough to be near a coast through which millions of birds migrate, then a short study of Google maps will soon show you where the suitable habitat is.

You might have to be up before the working day, but if you bird where you can easily get to, in an area with the right characteristics – like a bunch of isolated bushes or a thick hedge connecting habitats – then you can find your own birds.

I often sit in my car watching a hedgerow where the other birders start their 5-mile circuit. Once they’ve all headed off and the dog walkers have hurried home, I have been treated to migrating west coast specials on the east coast and highland denizens in the marshlands. On the best of days I’ve lost count of the Willow Warblers and Whitethroats, Blackcaps and Chiffchaffs, and have sometimes been treated to Ring Ouzels, Pied Flycatchers or Redstarts, none of which reside there.

Remember, birding hot spots attain their status because lots of good birds are seen there. In other words, lots of people watch the area, or some people watch it a lot. There may, indeed there MUST, be lots of places which the birds frequent but are not watched much of at all. In recent years when the hoards are heading for the Scilly Isles some intrepid birders head for the Western Isles. These explorers have turned up some terrific birds in the Hebrides. In the Scilly season there are thousands of people per square mile, in the islands off western Scotland there can be many square miles to the person.

In my home county of Kent there are some increasingly famous spots, which, a year or two ago were hardly watched. Now they get the coverage of a handful of dedicated (and it has to be said very good) birders and they turn up some stonking birds.

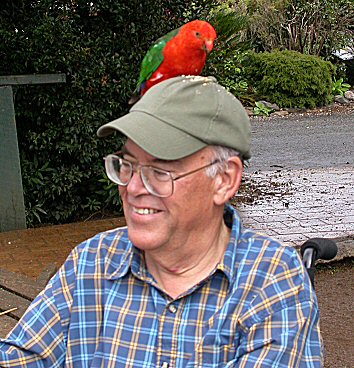

Brian did not have to wheel far for this one – a King Parrot outside O’Reilly’s near Brisbane

What you hear is what you get…

Did I mention I couldn’t walk very far? Yes, I know I did, but I have lately developed another encumbrance. I’ve gone deaf in one ear. This is really annoying, as I’ve lost ‘binocular’ hearing. I can still hear the squeaks, peeps and whistles, but can no longer tell where they are coming from. I turn my head this way and that like a hawk watching for mouse movements. Sometimes I manage to pinpoint a call, but I have always had another disability – a ‘tin’ ear. By which I mean that, no matter how much I try, I cannot commit song to memory. Its not just bird song – you should hear me mumble the popular songs of the seventies, with luck I carry the chorus but then I have to make the rest up!

Continued exposure means that if I sit in my urban yard I can tell a robin from a song thrush from a blackbird. However, if you plonk me down in a spring wood the same songs will all sound fresh and new and totally unidentifiable.

I hesitate, therefore, to give this advice but, one of the major weapons in the sedentary birder’s locker is the ability to recognize a bird by its utterances.

The thing is, that the yompers are less likely to pick up on song as their very passage both creates noise and stifles singing. Many birds go quiet when they fear human presence although some will skedaddle with their very own alarm calls. For us skulkers an ingested songbook can double the birds we note, especially as our tranquility encourages normal bird behaviour and increases the distance from which a call will carry to our ears.

Concessions…

I have not been exhaustive in my description of techniques of use to the challenged, corpulent or bone-idle birder. But there is one more string to this bow. Service providers, such as the RSPB (no doubt nudged by the likes of ‘Birding For All’) are getting better at enabling those with mobility problems to get to where the birds are.

On some reserves, tracks can be driven to otherwise unattainable hides (don’t be put off by the stares of the self-important striders). In others mobility scooters are available and, at still others, good design means that birders can be inside looking out, rather than outsider looking in, meaning that a disabled birder doesn’t have to walk far to be in the heart of the action.

Now, where did Hawkeye hide those M&Ms?